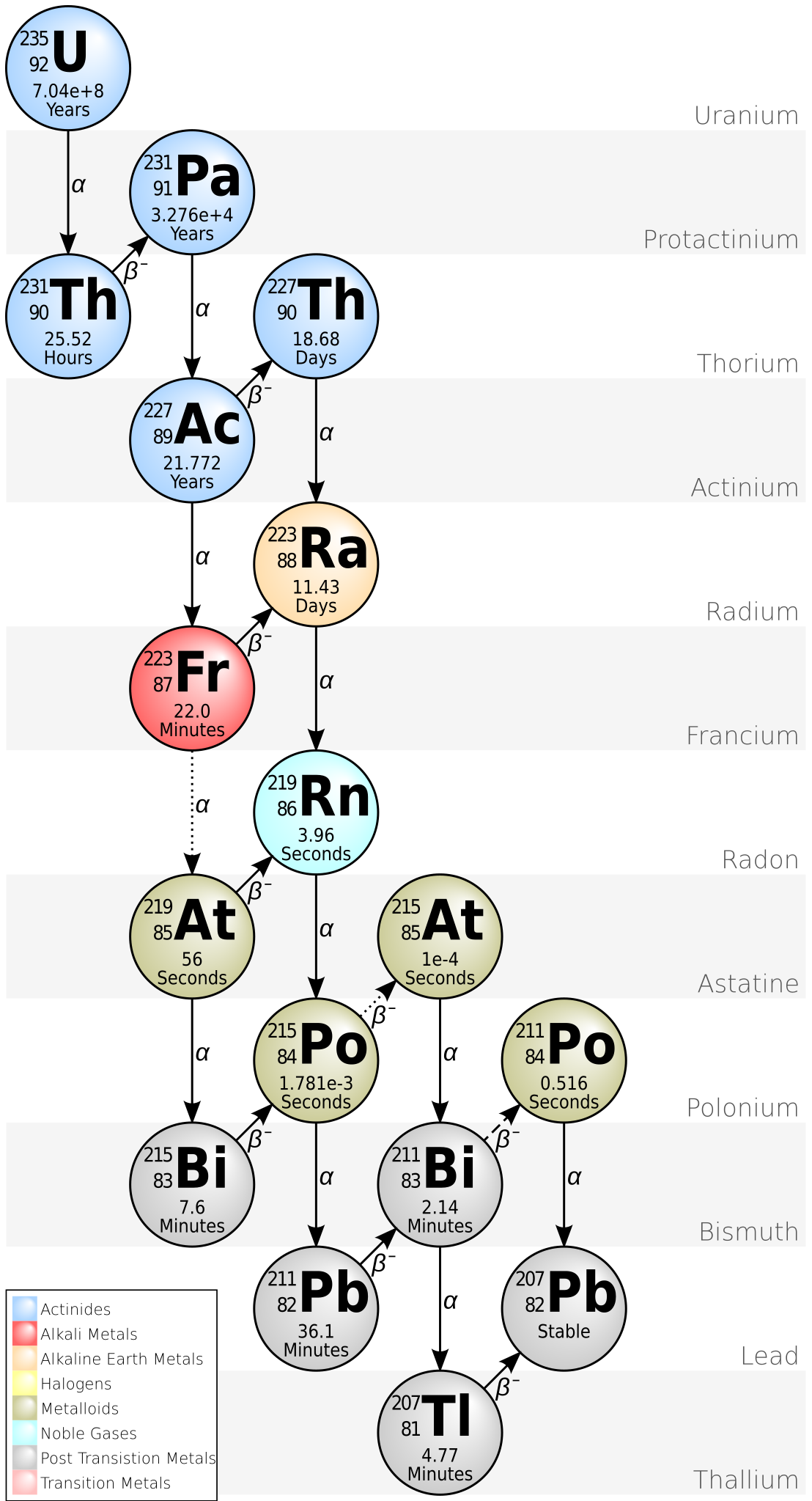

Here you can see what Meitner was studying: the decay chain starting with uranium-235 that produces protactinium, then actinium, and eventually lead. All the nuclei in this decay chain have atomic mass 4n+3. The reason:

• In "α decay" a nucleus emits a helium nucleus or "α particle" - 2 protons and 2 neutrons - so its atomic number goes down by 2 and its atomic mass goes down by 4.

• In "β decay" a neutron decays into a proton and emits a neutrino and an electron, or "β particle", so its atomic number goes up by 1 and its atomic mass stays the same.

But to understand Meitner's work in context, you have to realize that these facts only became clear through painstaking work and brilliant leaps of intuition! Much of the work was done by her team in Berlin, Marie and Pierre Curie in France, Ernest Rutherford's group in Manchester and later Cambridge, and eventually Enrico Fermi's group in Rome.

At first people thought electrons were bound in a nondescript jelly of positive charge - Thomson's "plum pudding" atom. Even when Rutherford, Geiger and Marsden shot α particles at atoms in 1909 and learned from how they bounced back that the positive charge was concentrated in a small "nucleus", there remained the puzzle of what this nucleus was!

(2/n)